It’s 2018. NASL is dead. Jack Cummins is dead. Left without a leader, NISA falls back to a committee to select its new head. The list of candidates are compiled with Peter Wilt’s help, his last work with the league front office. Wilt then departs Rebel Nest and NISA to found Forward Madison in USL.

And then, seemingly nothing happens. Nobody hears from NISA for an entire year. Their press release at the start of the process included the line “The National Independent Soccer Association was a United States based professional soccer league preparing to launch in the spring of 2019.” We all closed the mental book on NISA as a tragic failed launch.

It’s now 2019. NISA has undergone multiple changes of leadership since losing Rebel Nest. John Prutch of Club 9 Sports had been charged with leading the committee to select the new leader, and in the end, John Prutch became the new commissioner. Yes, this is the same Club 9 Sports that originally stated that it would be a conflict of interest for them to lead the league due to their consulting business. From here on out, the Prutch family would occupy several key positions, serving as the public face of the league office.

In April, the NPSL had announced the creation of the Founder’s Cup, frequently known as NPSL Pro. NISA announced their relaunch at the end of May. With cooperation seemingly over, it was now a race between the two leagues to have a stronger Fall launch than the other and prove that their model would work. NPSL promised to buck the PLS entirely, while NISA promised to start from division three and eventually build out their own division two and one leagues.

According to the NISA Operating Agreement, 60% of the league was now to be owned by its member clubs, and 40% would be owned by other investors. The board would consist of the team owners and their representatives, with the league’s president and commissioner reporting to the board directly. In theory, the teams would share equal votes to control the league- this was also part of the pitch from version zero, which explicitly said that the clubs would have 100% control of the league. In practice, version zero’s original proposal for Class A, B, and C shares to control voting rights had apparently been abandoned for this 60/40 split- and future events would cast doubt on the idea that all teams had equal votes.

This structure was meant vaguely similar to that of the Premier League’s, where the 20 member clubs also have one vote each on the board and control the league directly. However, relegation from the Premier League would result in your vote being given to a team that had been promoted into the league, so only those clubs that are actually playing in the league have a say. NISA does not appear to have a mechanism for this. Expansion and membership fees were needed to fund the league office itself, which meant that clubs were not earning or losing their position, but buying equity in the league. This meant that a team that was approved for expansion and later was unable to take the field would continue to be listed as a “NISA Member” even while on hiatus.

This made even basic questions like “how many teams are in this league?” difficult to answer. Teamsterz have been accepted and they’re on the league website, but they’ve never kicked a ball- are they in the league? Atlanta SC played one half-season and then nobody has ever heard from them again- are they in the league? What does it mean to be in NISA? Judging from the website, it meant anyone who had bought equity and was claiming they’d play again at some point. USSF’s mandate for a minimum of 8 teams in a division 3 league would probably not accept the same definition- but if they would, NISA would be set for life on that requirement.

The Fall 2019 season would be known as the NISA Showcase- a quickly-organized half-season where east and west would win playoff berths in the Spring 2020 half-season to come. There were no fall playoffs- standings on the table would decide the ultimate winners. Unfortunately, the football on the pitch wouldn’t dominate the headlines around the season. Two clubs would meet their ends during or after the Showcase: Atlanta SC, and the Philadelphia Fury.

Atlanta SC

With the 2019 relaunch, John Prutch stated that there were over 100 metro areas without pro soccer in their communities. These were the ideal targets for NISA: underserved communities, places that deserved their shot in the game without franchise limits locking them out for not being on a marketer’s prime target list. Atlanta was not one of these areas. Atlanta United, at the time of this writing, is the strongest supported MLS team in the country. Their stadium was regularly packed before the pandemic.

Not everyone in the Atlanta area was happy with this state of affairs. Before Atlanta United, the Atlanta Silverbacks had existed since the 90s, most recently in a professional run in the NASL. When the NASL side left, their NPSL reserve side was allowed to license and adopt it- until finally their licensing agreement expired, leaving them as “Atlanta SC”. But make no mistake- the Silverbacks had been dead well before this, regardless of who was using the name. Many in the independent movement jeered at Atlana United supporters as being plastic, as having been unwilling to support the perfectly good Silverbacks and only showing up when MLS came to town.

They weren’t wrong in their criticism, but being right isn’t enough to turn back the hands of time. United was here, it was entrenched, and a lower-budget option with a cheap logo wasn’t going to cut it. Atlanta SC played for the Fall Showcase, then pulled out before 2020, promising to return soon. They never did- the team is now dead, the last remnants of the Silverbacks’ legacy falling in their effort to climb above the NPSL.

It’s November 2021 as I write this. NISA’s header still lists a generic “NISA Atlanta” as a member club, with no website. Officially, the last anyone has heard from the league maintains that Atlanta is still being worked on and the market, if not the club, will be returning to play. There are over 100 metro areas in the US that don’t have pro soccer in their community- but this would not be the last time that NISA and its member clubs tried to splice the haves rather than delivering to the have-nots.

Philadelphia Fury

For as much as Detroit City FC embodied idealism to so many in the movement, the reason the club has been able to occupy that stance was due to canny business pragmatism that kept the lights on. While the club would do everything it can to make NPSL Pro work, our first match against a NISA club was in the Fall of 2019 with a friendly against the Philly Fury, keeping the lines of communication open to NISA just in case. The match would be decided 1-0 in favor of City, with supporters also having their fun toying with the Fury in classic NGS fashion.

The original Philadelphia Fury had played in the original NASL. Throughout this blog, when I’ve said “NASL” I mean the division 2 league that played from 2011 to 2017. That league derived its name from an earlier incarnation, the 1968-1984 NASL that functioned as the top league in the country throughout its existence. The original Fury played from 1978-1980 in what many have started to call “NASL 1.0”, in contrast to the 2010s “NASL 2.0”. In the end, the club’s demise would come in the form of relocation to Montreal.

The revived Philadelphia Fury was another instance of a NISA club attempting to splice the haves instead of delivering to the have-nots. While not nearly as well-supported as Atlanta United, Philly was focused on the Philadelphia Union. Unlike Atlanta, there was not a strong rallying cry to an independent alternative for the Fury to claim the legacy of. While the team and its name did have a history in the area across many leagues, they also carried a poor reputation to most observers as an unserious team that underperformed.

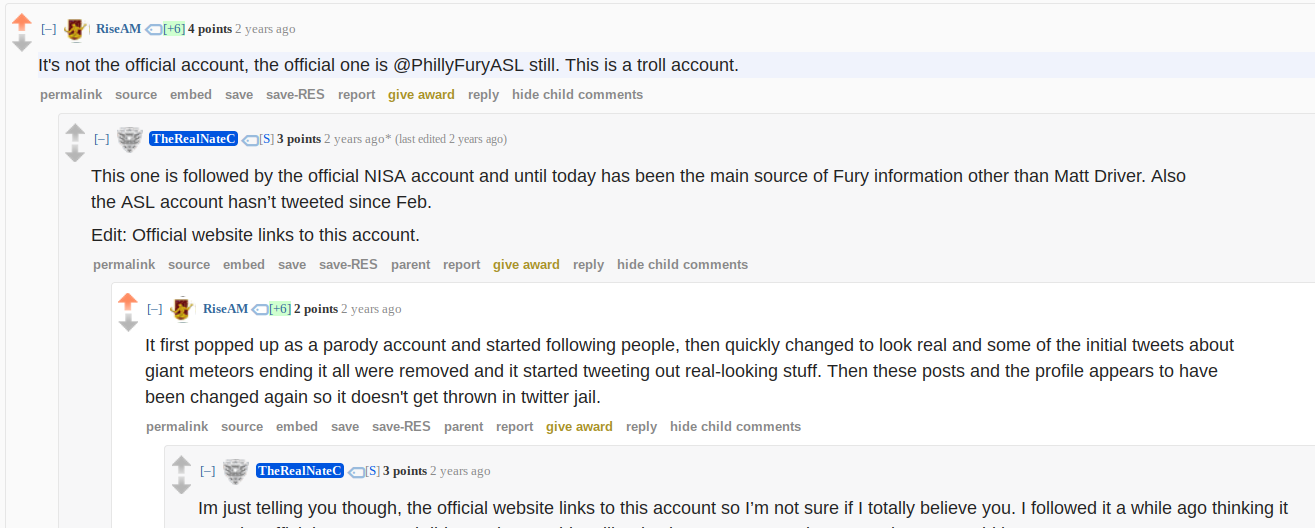

Months ahead of the match with City, NGS members noted that the Fury was calling for tryouts on a remarkably short timespan for how soon NISA would begin playing. The Fury also had no social media presence to speak of and was in need of a social media manager for that. Or, depending on how you looked at it, they had too much social media presence already. Every time the Fury moved to a new league or started a new initiative, they created a brand new Twitter account, abandoning the history of their previous one and creating a fragmented and confusing social media presence. For most people, this was just something to shake their heads at and sigh about. Another league with clubs run amateurishly, without competition we could take seriously. For me, this was the start of a bad idea.

If someone were to register a @PhillyFuryNISA account, it would fit right in with the previous official ones. I knew people who had run plenty of troll or fake accounts that had fooled people into believing that they were the real deal, and I wanted to see if I would be up to the challenge. So, while resting in a hotel room in Chicago between our other destinations, I registered the account and set it up as the official presence of the NISA iteration of the Fury.

I had a few rules and guidelines for how I would make this look convincing. First, I would make sure I posted at least one new thing every day to generate a consistent stream of buzz. Second, any official news around the Fury (such as from head coach Matt Driver’s account) would be set to notifications so I could immediately repackage it in my own words. Third, I would explicitly tie this iteration of the Fury to its NASL 1.0 origins to build a sense of history and establish it as having more history than the Philadelphia Union. Fourth, I would follow everyone that Matt Driver and the previous Fury accounts had, in addition to anything that NISA’s league account was.

Within two weeks, this strategy proved to be wildly successful. NISA followed me back and was retweeting most things I tweeted. People in the area followed this as the real rebirth of the Fury and engaged it with questions around season tickets and responded to potential giveaways. And then, one day, the account received a DM from Driver asking who was operating it, while the Fury website was updated to list my account as the official Twitter.

I immediately proceeded to post a series of shocking memes to confuse people. I could have chosen to not respond to the DM asking who was operating the account, but sooner or later the truth was going to come out anyway. In my mind, it was time to make good on the troll while that was still an option.

Reddit picked up the story and some refused to believe that this hadn’t been the real account the whole time, even when told verbatim that it had always been a troll. The website was corrected within the day, but for months afterwards attempts at tagging the Fury would go to the troll account instead of any real one.

This wasn’t the worst thing that happened to the Fury that year, however. In their first NISA game, an empty stadium bore witness to Miami FC smashing the Fury 8-1. The loss proved to be the final straw, with the primary team owner pulling out from the team immediately. The Fury was forced to forfeit every remaining game, and NISA voided the results from other games to make up for the schedule imbalance. Miami FC vs Oakland Roots did not give points to Miami, and California United VS San Diego 1904 FC did not count for California United.

The Fury promised to return in 2020 after reorganizing, but they have never returned as a professional squad. In 2020, they appeared briefly on the website as a component of Matt Driver’s next initiative, Soccer Universities, which I’ve linked to at the bottom of this article. Soccer Universities has claimed that they “will completely disrupt the college system here in the USA and abroad.” I’ll leave it to you to read through their website and evaluate this claim for yourself.

The Showcase ends

Thus ended the NISA Showcase. Two of its teams, the Oakland Roots and Miami FC, had only joined for the Fall because of NPSL Pro’s insurance situation. Having started with the minium 8 teams, the departures of Atlanta SC and the Philly Fury would drop NISA to 6 teams, a death sentence for sanctioning. It’s possible that if NPSL Pro had been able to get insurance for its mix of professional and amateur players, that NISA would never have been able to play their Fall season. Despite claiming 10 member clubs in the Spring, not all of those had shown up for the Fall.

But that wasn’t what happened. The insurance problems that killed NPSL Pro became salvation for NISA, giving it the chance to get off the ground. Four of the remaining clubs from the NPSL Member’s Cup would migrate into NISA, putting NISA back over the PLS requirement and into safety for the Spring 2020 season. Those four clubs were the strongest potential advocates from within NPSL for cooperation with NISA’s new system- and with their departure, any hope for cooperation between the two leagues was forever gone. NISA would continue to look for approaches to work with the amateur leagues, but version zero’s hoped for partners were forever separated.

But Spring 2020 was not going to be the season where things settled down into a comfortable new normal. There are worse dangers to a club than league in-fighting or MLS bids threatening to overshadow everything. Detroit City FC was poised for its next phase of growth, but the COVID-19 pandemic would threaten to destroy the club instead.

Additional reading and sources: